a call to imagination + a final bow

Spoiler-Free:

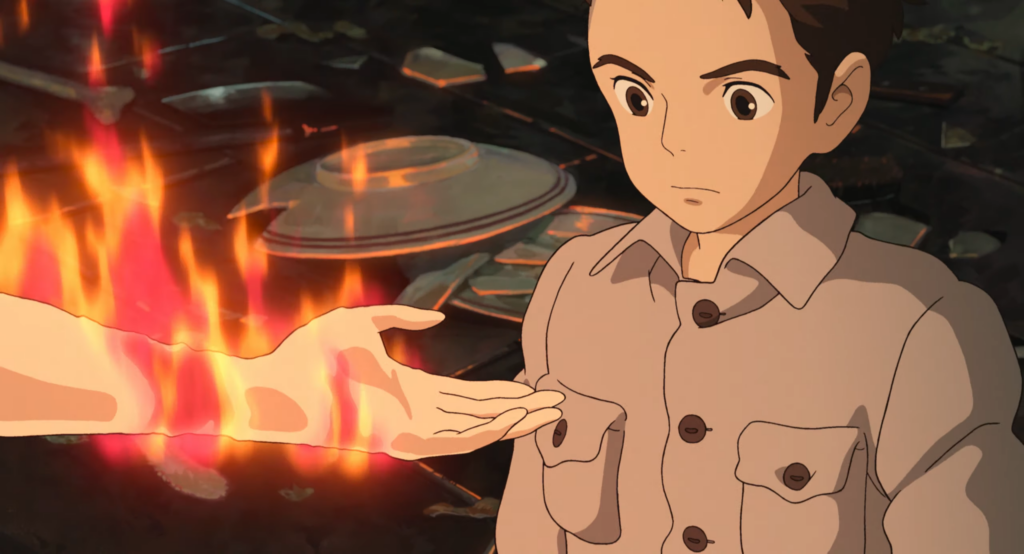

Hayao Miyazaki's likely final picture, The Boy and the Heron, has inspired confusion in many viewers and reviewers. But that has not been the experience for all, and it has not been mine. The tale of a boy who loses his mother in Tokyo in WWII before moving to a countryside estate - a location that serves as the catalyst for mysterious events and adventure - The Boy and the Heron is, in many ways, the best example of a complete children's fantasy story in Miyazaki's oeuvre - alongside the Oscar-winning Spirited Away.

Plot aside, The Boy and the Heron boasts flawless voice acting (with the possible exception of Dave Bautista), including Robert Pattinson's ubiquitously-praised turn as the titular Heron. Taking the time to appreciate Pattinson's work, one finds emotional nuance, beckoning subtlety, and a fully fleshed-out character in the Heron. Although his cadence and tone fluctuate along with the character's state of mind, his vocal work never strays from the persona of the Heron. Although much has already been said about Pattinson's work, not enough has been said about that of Florence Pugh's stellar work as the old house maid Kiriko. Do yourself a favor if you see the film, and take the time to savor her work.

The Boy and the Heron's score also boasts resonant themes that feel familiar but are still stirring (one section brings to mind a Hamilton melody). And the visuals of the film - oh, the visuals. The Boy and the Heron is perhaps the most beautiful movie I have seen; if not, it is certainly among the top. With expertly hand painted backgrounds, one feels as if they can smell the wood, feel the textures, and catch the gold glinting off of the interiors on the estate. And the fantasy landscapes strike so many notes, filling dreamland desires fantasy lovers didn't even know they had.

Returning to the plot, the complaint of many seems to be: "I didn't get it. There were so many things happening, and they were just too weird." I find this reaction disheartening and surprisingly similar to the reactions of the imagination-free parents in many children's fantasy tales. When the adventurer returns, parents shake their heads at the children's nonsensical stories or patronizingly pat their heads. It would be a truly sad state if we, as consumers of art, have lost the ability to enjoy stories of pure imagination

...or if we have gotten to the point of demanding "it all to make sense." Miyazaki's giant murderous parakeets? The sequence of events surrounding the blobby warawara? (As if the Duchess making the pig she's nursing sneeze by excessive pepper grinding - or the majority of Alice in Wonderland - ever made much sense).

"'Well, perhaps your feelings may be different,' said Alice

'all I know is, it would feel very queer to me.'

'You!' said the Caterpillar contemptuously,

'Who are you?' Which brought them back again

to the beginning of the conversation."

The story of the Boy and the Heron is such a clear indulgence in imagination - the type we are rarely given of late (at least in film; one only needs to watch the trailer for the most recent computer animated children's movies to recognize the disparity) - and done by one of the greatest children's/fantasy/general filmmakers of the century. The fact that people aren't rejoicing at the opportunity to see such "absurd" levels of imagination leaves me, frankly, sad. This is particularly surprising considering how many correlations there are between The Boy and the Heron and other beloved, often absurd, classics in imaginative fantasy.

Spoiler-full:

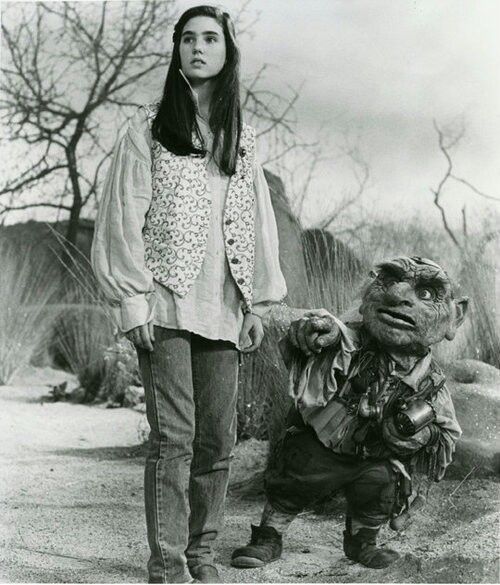

The character of the heron seemed directly influenced by Hoggle from Jim Henson's Labyrinth. Both characters spend much of their films determinedly refusing to consider the main character a friend only to be moved by the hero's naming them as such near the end of their tales.

"I'm not your friend or ally, kid." - The Boy and the Heron

"Hoggle ain't no one's friend." - Labyrinth

As in classics like Alice and The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, The Boy and the Heron is a tale of a child passing through a doorway into a magical land full of strange characters and danger, forced to become heroes before ending up back in the worlds they know. As in the Wizard of Oz, the main character returns to their real life to be met with concerned side characters who had been present in different forms in the magical land. These are well-known formulas, but rarely do we seen them done this well in modern media.

As the story goes, Miyazaki came out of retirement because he wanted to make something for his grandson. Beginning there, the meaning of the film becomes clear. Mahito's great-uncle has been locked away in a mysterious tower for decades, using laser-like care and precision in minutia to keep the worlds he has built alive (a likely reference to Miyazaki's own reputation as being an extreme stickler with the details of his projects). The great-uncle spends the film attempting to find an heir who can take over his role, while also acknowledging that what he makes isn't perfect, because he isn't a perfect man. In a somewhat surprising turn of events, Mahito chooses not to take up his great-uncle's reign, letting the worlds fall apart. The tower itself and all of the passages and doorways to magical lands it housed crumble. Perhaps this is Miyazaki's way of framing the knowledge that Studio Ghibli may now be officially dead, that once he is gone, the worlds he has built (and the imagination he has) will likely be gone as well. It is bittersweet, softened somewhat by the fact that Mahito keeps one of the blocks his great-uncle used to build his worlds, perhaps carrying with him the ability to continue the creative work one day if he chooses.

As in Looking Glass land, many possibly random things transpire - things which may only exist because they pleased the imagination of the creator. I do believe that much meaning can be found within the story's "random" events and characters. Mahito's mother, who died in a fire, has the power of fire within the tower world, and there may be many more such connections for those inclined to look. No matter one's age, the imagination is full of nonsense, and much of that nonsense has meaning. But the meaning isn't the point. May we as moviegoers, as art absorbers, be more like the professor at the end of the Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe.

"The Professor, who was a very remarkable man,

didn't tell them not to be silly or not to tell lies,

but believed the whole story. 'No,' he said,

'I don't think it will be any going trying to go back

through the wardrobe door ... don't go trying to use the same

route twice. ... How will you know? Oh, you'll know all right.

Odd things, they say - even their looks - will let the secret out.

Keep your eyes open.'"

If Miyazaki had remained in retirement, no one would ever have been able to experience this masterpiece in creativity, and that is a thought that brings tears to my eyes. I don't claim to have loved every one of Miyazaki's films, but he has made several all-time favorites, and it is undisputed that his work has inspired modern animation and children's filmmaking in countless ways. Being able to see The Boy and the Heron in the theater made me feel so deeply grateful. It is the the curtain-call of an as-yet incomparable master, a giant in the world of art, a man who was never afraid to tell stories about unexpected topics with unexpected elements and unexpected heroes/heroines. Watching the ending to The Boy and the Heron felt much like watching the final scene of The Truman Show. It brought the feeling of swelling music, of triumphance, as the one we all love walks through an untried door, into the next phase of reality, where we will not be permitted to follow.